Marvelous Masonry - Celebrating Masonry’s Heritage: The Medieval City of Guimarães, Portugal

Words: David BiggsDavid Biggs, PE, SE

As seen from past articles, the world has a wealth of marvelous masonry! Our masonry heritage defines us as a culture. No other building material can make that claim. In February and March 2023, I had the privilege of working at the University of Minho (min-yo) in Guimarães, Portugal. The U.S. Department of State and the Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board provided me with a Fulbright Specialist Program award to be a lecturer/consultant at the university for the International Advanced Master’s program titled Structural Analysis of Monuments and Historic Construction.

I’ve admired Guimarães since my first visit in 2010. Guimarães was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2001, was the 2012 capital of European culture, and in 2013 was the European City of Sport. The Portuguese consider Guimarães the birthplace of Portugal. In fact, on one of its walls, there is a quote that makes it clear “Portugal Was Born Here.” These credentials alone make the Medieval City of Guimarães a must-see location in Portugal and worthy of the designation of Marvelous Masonry.

UNESCO (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1031/) states that

“The exceptionally well-preserved Historic Centre of Guimarães, located in the northern Portugal district of Braga, is often referred to as the cradle of the Portuguese nationality. The history of Guimarães is closely associated with the creation of the national identity and language of Portugal. The city was the feudal territory of the Portuguese Dukes who declared the independence of Portugal in the mid-12th century.

Founded in the 4th century, Guimarães became the first capital of Portugal in the 12th century. Its historic center is an extremely well-preserved and authentic example of the evolution of a medieval settlement into a modern town, its rich building typology exemplifying the specific development of Portuguese architecture from the 15th to the 19th centuries through the consistent use of traditional building materials and techniques. This variety of different building types documents the responses to the evolving needs of the community. A particular type of construction developed here in the Middle Ages was used widely in the then-Portuguese colonies. It featured a ground floor in granite with a half-timbered structure above, a technology that was transmitted to Portuguese colonies in Africa and the New World, becoming their characteristic feature.

The Historic Centre of Guimarães is distinguished in particular for the integrity of its historically authentic building stock. Examples from the period from 950 to 1498 include the two anchors around which Guimarães initially developed, the castle in the north and the monastic complex in the south. The period from 1498 to 1693 is characterized by noble houses and the development of civic facilities, city squares, etc. While there have been some changes during the modern era, the historic center of Guimarães has maintained its medieval urban layout. The continuity in traditional technology and the maintenance and gradual change have contributed to an exceptionally harmonious townscape.”

Portugal is a masonry country and granite is the most used stone. Every city and town have marvelous examples of historic craftsmanship. Let us take a tour through Guimarães.

Medieval City Walls

Guimarães was founded in the 10th century. But archeological findings indicate there were permanent settlements in the area during the Copper Age (c. 4000 BC) and the Romans occupied the region during the reign of Trajan (98–117 AD). Defensive walls were built to surround the city by the 1200s. However, as the city grew most of the walls were torn down in the 1400s to link the center city with the expanded areas outside. Today, visitors can still enjoy portions of the walls (Figures 1 and 2) and the remaining towers. The tower in Figure 3 pronounces "Aqui nasceu Portugal" or Portugal was born here. The construction is granite with aerial lime mortar.

Figure 1: Guimarães - City walls from exterior

Figure 1: Guimarães - City walls from exterior

Figure 2: Guimarães - City walls from the interior with visitor walkway along parapets

Figure 2: Guimarães - City walls from the interior with visitor walkway along parapets

Figure 3 – One of the remaining towers proclaims, Portugal was born here

Figure 3 – One of the remaining towers proclaims, Portugal was born here

Castle of Guimarães

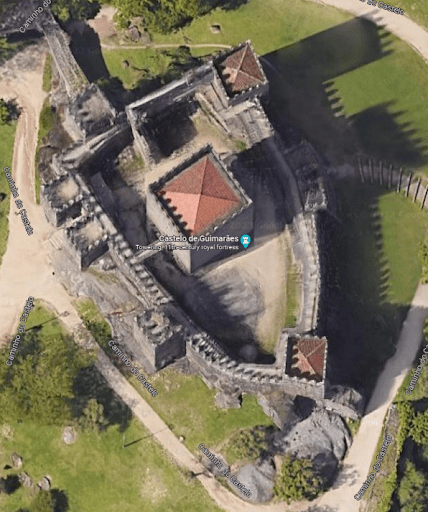

Records indicate a wooden castle was first constructed in 968 AD to protect the local monastery and settlement. By the late 11th century, the castle began its transformation to a stone structure, and the castle was completed by the end of the 13th century to the pentangular configuration we now see (Figure 4 – North elevation is lower left) with the eight square towers (Figure 5). The granite and lime mortar has survived centuries.

Figure 4 - Castle of Guimarães (courtesy of Google Earth)

Figure 4 - Castle of Guimarães (courtesy of Google Earth)

Figure 5 – South Elevation

Figure 5 – South Elevation

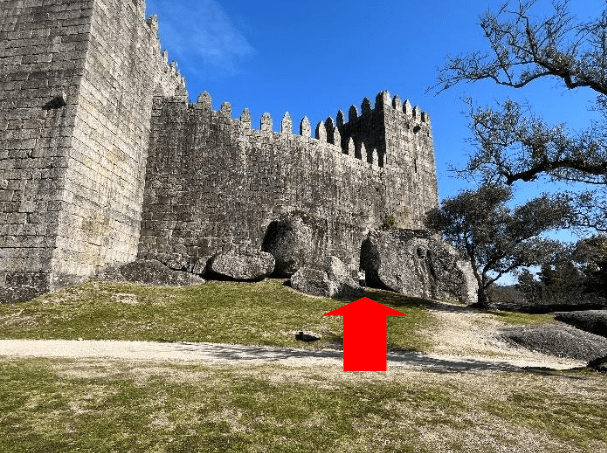

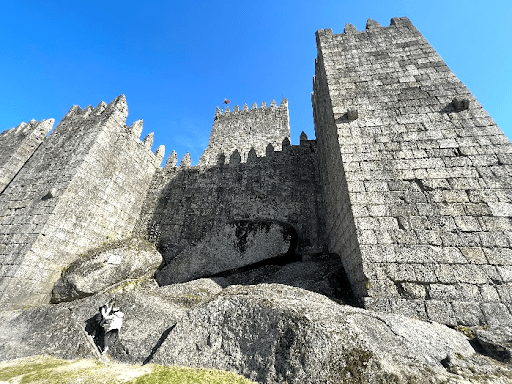

The castle was constructed of cut granite blocks and founded on massive granite outcroppings (Figures 6 and 7). The masons had to cut and shape the castle stone to the profile of the rock. The walls are up to 6 feet thick.

Figure 6 – North Elevation on granite outcroppings

Figure 6 – North Elevation on granite outcroppings

Figure 7 - Outcroppings

Figure 7 - Outcroppings

From the interior, it is possible to walk the parapets and see the marvelous stone up close. Figure 8 shows walkways in 2014 with no railing protection. By 2023, railings had been installed. The granite outcroppings are also visible.

Figure 8 – Walkways (no protection) 2014

Figure 8 – Walkways (no protection) 2014

Figure 9 – Walkways with protection 2023

Figure 9 – Walkways with protection 2023

The parapets are quite interesting. Each one is 18” thick, 5’-4” tall, and 28” wide. They adorn the walls and the towers (Figure 10). Figure 11 shows a close-up. The lifting holes are visible on many stones. There is no anchorage for the stones; they are only mortar bedded.

Figure 10 – Parapets and stairs

Figure 10 – Parapets and stairs

Figure 11 – Parapet

Figure 11 – Parapet

Starting in the late 1600s the castle was losing its importance as a defensive fortification and recommendations were made to protect it, but no action was taken. Demolition was proposed in 1836 and the stones were to be used to repave the city streets, but again that proposal was defeated. Finally, in 1910, the castle was declared a national monument despite its poor condition. That led to a restoration starting in 1936 and its re-inauguration in 1940. A major problem was that the fissures in rock outcroppings (Figure 7) had continued to move, causing cracking the full height of the walls that rested on the outcropping. The outcropping was anchored with drilled-in bolts to sound rock below and cement grouted, and the fissures infilled. The cracks in the wall were stabilized through grouting and pointing.

So, the granite masonry castle has weathered centuries with little to no maintenance and is still a marvelous masonry structure.

Palace of the Dukes

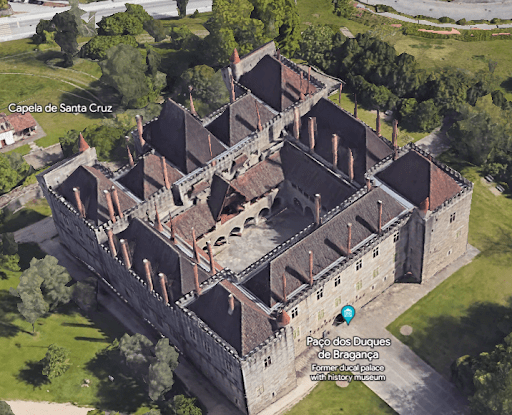

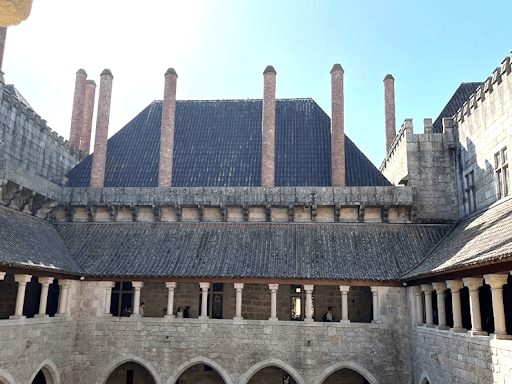

The palace was constructed for the Bragança family in the early 1400s who occupied it for about a century. In the mid-1600s, the Braganças became the Royal Portuguese family. However, the building was progressively abandoned until it was used for military purposes during the 1800s and finally underwent restoration from 1937 to 1959. Figure 12 shows the palace and the 39 brick chimneys. It is a national monument.

Figure 12 – Palace of the Dukes (courtesy of Google Maps)

Figure 12 – Palace of the Dukes (courtesy of Google Maps)

The palace has changed over the centuries. Damaged areas were rebuilt; the rear was rebuilt from a one-story section that we see today. Only four chimneys are original and functional, the remaining ones were installed in the 1937 renovation and do not function. Figure 13 shows various chimneys from the interior courtyard.

Figure 13 – Chimney viewed from the courtyard

Figure 13 – Chimney viewed from the courtyard

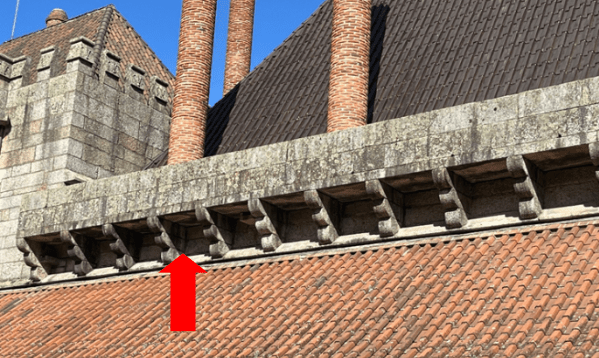

The operational chimneys service the fireplaces. Figures 14 and 15 show the ornate granite craftsmanship. The cantilevering stone (arrow) is impressive.

Figure 14 – Fireplace

Figure 14 – Fireplace

Figure 15 – Close-up of chimney

Figure 15 – Close-up of chimney

Figure 16 shows the base of one of the non-functioning chimneys. This specific one bridges the roof gutter, while others are constructed on the parapet.

These 4-foot diameter chimneys are as tall as 27 feet. The bricks are approximately 7 inches thick. Their stability is dependent on the weight of the chimney to resist wind loads (earthquake loads in this part of Portugal are low). One of the west-facing chimneys developed a lean and had to be pinned to its base with drilled and grouted rods.

Figure 16 – Base of non-functioning chimney

Figure 16 – Base of non-functioning chimney

Figure 17 – 27-foot-tall chimneys

Figure 17 – 27-foot-tall chimneys

Although most chimneys are in good condition, several are eroded from moisture damage (Figure 18) or cement mortar that is too hard (Figure 19). Repairs include brick patching, replacement, and repointing.

Figure 18 – Eroded brick

Figure 18 – Eroded brick

Figure 19 – Damaged brick from cement mortar

Figure 19 – Damaged brick from cement mortar

The palace has numerous ornate stone details as noted such as the fireplaces (Figure 15). In addition, there are:

- Corbeled cornices (Figure 20, arrow) that support the parapets.

Figure 20 – Stone cornice

Figure 20 – Stone cornice

- Stone brackets that support timber framing (Figures 21 and 22). These are used interior and exterior.

Figure 21: Stone Brackets

Figure 21: Stone Brackets

Figure 22 – Stone brackets

Figure 22 – Stone brackets

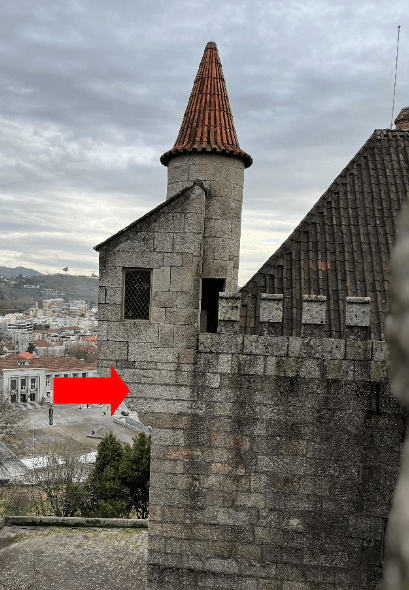

- Corbeled towers (Figure 23). There are two of these. The stability of the cantilevered stone (arrow) is amazing. The adjacent round tower must be supplying some balancing weight. Throughout the palace, no cracking was observed in any of the cantilevering stones which is an indication of the quality and strength of the granite stone.

Figure 23 – Corbeled towers

Figure 23 – Corbeled towers

- Carved window seating (Figure 24). These are throughout the palace.

Figure 24 – Window seating

Figure 24 – Window seating

- Parapet stones (see Figures 17 and 25). The exposed surfaces have ornate carvings.

Figure 25 – Parapet carvings

Figure 25 – Parapet carvings

- Arches and lintels (Figures 24, 26 to 30).

Figure 26 – Chapel entry

Figure 26 – Chapel entry

Figure 27 – Stairwells and hallways

Figure 27 – Stairwells and hallways

Figure 28 – Upper lintels

Figure 28 – Upper lintels

Figure 29 – Interior arch

Figure 29 – Interior arch

Figure 30 – Courtyard arches (lower); Chapel entry (upper)

Figure 30 – Courtyard arches (lower); Chapel entry (upper)

- Floors and pavers (Figures 31 and 32). All of the interior floors are brick pavers in a herringbone pattern while the exterior has granite pavers.

Figure 31 – Interior floors

Figure 31 – Interior floors

Figure 32 – Exterior pavers

Figure 32 – Exterior pavers

Medieval City Center

The city center is a museum with its marvelous buildings. In addition, there is an archeology museum that has many masonry artifacts.

Archeology Museum

The museum is housed in the 14th-century Gothic cloister of the church of São Domingos. The collections include prehistoric and proto-historical archaeology, epigraphy, and numismatics. One of the most important pieces is a stele (a stone or wooden slab, generally taller than it is wide, erected in the ancient world as a monument) known as the Pedra Formosa (the Beautiful Stone) which was a wall of a pre-Roman bathhouse (Figure 33).

Figure 33 – The Beautiful Stone (approximately 6 feet tall) from a pre-Roman bathhouse

Figure 33 – The Beautiful Stone (approximately 6 feet tall) from a pre-Roman bathhouse

Of the many artifacts, there are numerous Celtic remains including carved stone elements and grave markers (Figures 34 to 36).

Figure 34 – Museum stone artifacts

Figure 34 – Museum stone artifacts

Figure 35 – Celtic carvings

Figure 35 – Celtic carvings

Figure 36 – Celtic carving

Figure 36 – Celtic carving

City Center Buildings

The medieval buildings date to the 1500s and earlier. There are beautiful squares and plazas. The traditional buildings are granite at the first level and timber framed above, often with balconies; others are all granite (Figures 37 and 38).

Figure 37 - Plaza

Figure 37 - Plaza

Figure 38 – Plaza

Figure 38 – Plaza

There are various monuments and shrines throughout the city (Figures 39 and 40). The roofs are often vaulted.

Figure 39 – Shrine

Figure 39 – Shrine

Figure 40 – Shrine

Figure 40 – Shrine

Portugal is a Catholic country and there are historic churches in every city (Figures 41 through 43). One feature to notice is the open bell towers. Another marvelous masonry feature is the use of blue Portuguese tile on many buildings (Figures 42 arrow and 43).

Figure 41 - St Peter Sao Pedro Basilica Church (1750)

Figure 41 - St Peter Sao Pedro Basilica Church (1750)

Figure 42 – Church of São Gualter (1600s)

Figure 42 – Church of São Gualter (1600s)

Figure 43 – Church of Saint Francis (constructed 1400 – 1743)

Figure 43 – Church of Saint Francis (constructed 1400 – 1743)

City Streets

Only in Europe would we consider discussing city streets as marvelous masonry. However, for all who have traveled, European streets and walkways are often masonries and not the concrete we find in the United States.

Figure 44 shows a quaint street in the medieval city. Here we see the random stone pavers. City utilities and drainage are buried beneath (see the conduits and downspouts) leaving that medieval character. The street does not accommodate autos; these streets would have only had cart traffic. Another feature is the overhead passageways between buildings, this is not common but does occur.

Figure 44 – Paved street

Figure 44 – Paved street

Sidewalk pavers are an art form in older European cities, including Portugal. Figures 45a through 45e show some historic patterns while Figure 45f is a modern variation. Once installed, these patterns need to be maintained following excavations or damage.

Figure 45a – Sidewalk paver

Figure 45a – Sidewalk paver

Figure 45b – Sidewalk paver

Figure 45b – Sidewalk paver

Figure 45c – Sidewalk paver

Figure 45c – Sidewalk paver

Figure 45d – Sidewalk paver

Figure 45d – Sidewalk paver

Figure 45e – Sidewalk paver

Figure 45e – Sidewalk paver

Figure 45f – Sidewalk paver

Figure 45f – Sidewalk paver

There is much more to discuss about marvelous masonry in Portugal. Stay tuned for future articles.

Acknowledgments

- I’d like to acknowledge my good friend Professor Paulo Lourenco of the University of Minho who invited me to the university and shared much of his work, and the added assistance of his staff with thanks to Ana Fonseca, Dr. Elisa Poletti, Dr. Daniel Oliveira, Dr. Alberto Barontini, and Dr. Vasco Bernardo, and support from the university.

- Support and assistance were provided by the Fulbright Commission Portugal from Dora Reis Arenga.

- Financial support was provided by the Fulbright Specialist Program with thanks to Courtney Indart and Catherine Coats of World Learning.

Author: David Biggs is a US-based consultant and regular columnist for Masonry (Marvelous Masonry series) and Masonry Design (Technical Talk) magazines. He is a PE and SE with Biggs Consulting Engineering, Saratoga Springs, NY, USA (www.biggsconsulting.net), and an Honorary Associate Professor with the University of Auckland, NZ. He specializes in masonry design, historic preservation, forensic evaluations, and masonry product development.